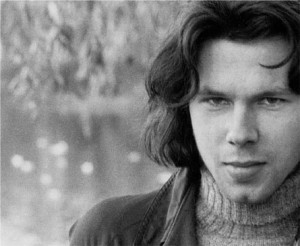

The legend of English folk singer Nick Drake extends to radio documentaries narrated by Brad Pitt, wave after wave of indie flicks and adverts plugging everything from cars to cough syrup which all feature his songs, and an army of celebrity fans that include R.E.M, Radiohead, Paul Weller and Jimmy Page.

Drake’s post-death acclaim is even fuelled by technology. Typing Nick Drake into Google returns 2.92 million hits; more than fellow dead musicians Ian Curtis (I.5m), Jeff Buckley (2.63m) and Eva Cassidy (1.63m). Nowadays, it seems everyone wants a piece of him. But it wasn’t always like this.

Criminally ignored in his lifetime, he died in November 1974, aged 26, of a drug overdose after a long battle with depression. The desolate beauty of his three-album career was the overlooked epitaph of a man who died utterly broken inside.

Nick Drake fever grows again this week when the touring concert Way To Bluestarts in Glasgow (before moving around the UK). The line up –organised by legendary American producer, and Nick Drake’s manager, Joe Boyd –will feature artists who worked with Drake or who have been influenced by him.

Stars slated to appear include Danny Thompson, Robyn Hitchcock, Teddy Thompson, Belle & Sebastian’s Stuart Murdoch, Lisa Hannigan and ’70s singer-songwriter Vashti Bunyan (whose own career has enjoyed a recent revival). Joe Boyd, who’s done more than anybody to posthumously promote Drake’s work, admits “it’s become nigh on impossible to separate the man from the music”.

If you know Nick Drake’s music and you know how he died, it’s easy to build a picture of a hopelessly depressive man incapable of finding happiness. But the people who knew Drake tell a different story. “As advertised, he was quiet,” says Boyd.

“But he was very smart, funny and determined. I had the pleasure of working with him and

he revelled in the experience of recording his first album [Five Leaves Left, 1969]. I was very fond of him.” Similarly, Danny Thompson, Pentangle co-founder and bassist on Drake’s debut album, remembers a diffident but engaging personality who enjoyed other people’s company. “He loved playing cards and staying up all hours. He knew all kinds of people,” says Thompson.

“Yes, he was shy, but I think he used to like that. I think he saw it as naughty.” Throughout Drake’s brief music career, his songs revealed a side to him he rarely showed in person. According to Robyn Hitchcock, Nick Drake “was like an inverse John Lennon”.

He goes on: “Instead of leaping to grab life by the throat, he shied away from the limelight.” Hitchcock says attempting to understand Drake’s character through his songs is like “trying to imagine an apple from a tree”. “One came from the other, but it doesn’t follow they must resemble each other,” says Hitchcock.

“The songs are a distillation of his personality, but it’s more complex than that.” One reason why so much time is spent analysing Drake’s psyche through his songs is because of the sheer lack of documented word from the singer. Only one interview is known to have taken place, a tortuous affair conducted by Sounds journalist Jerry Gilbert in March 1971. No other interviews with Drake have ever surfaced and for decades nothing was written about him. He remained a footnote of British folk music until concerted efforts were made to document his life. Previously, there was only the music.

“The songs do give an indication as to what he was thinking,” offers Thompson. “‘Man In A Shed’ [from Five Leaves Left] is obviously about a relationship he had. He’s asking the girl to come into his dilapidated shed to ‘stop the world raining on my head’. Maybe music was his shed, his shelter from the world.” Boyd agrees that Drake’s fatalistic world-view foretold he was doomed to be the forgotten man of his generation.

“The mystery is he could write a song like ‘Fruit Tree’ when he was full of optimism. It’s all very well looking at one of is final songs, ‘Black Eyed Dog’, and think it was written by a man waiting for death, but ‘Fruit Tree’ was written in the bloom of youth.” Composed when

he was still a teenager, the lyrics to ‘Fruit Tree’ are among Drake’s most prophetic: ‘Safe in your place deep in the earth/That’s when they’ll know what you were really worth.’ “It’s prescient how you can interpret that song as a roadmap of how Nick’s life turned out,” explains Boyd. “For me, ‘Fruit Tree’ is the central mystery. Logically, it should’ve been written by someone late in life.”

In February 1972 Drake released his valedictory masterpiece Pink Moonto little fanfare. He’d long since given up any attempt to promote his work, and the combined effects of

anti-depressants and vast quantities of marijuana made him withdraw further into himself.

“Dope was always a factor with Nick,” Hitchcock says. “It made it harder for him to bridge the gap between him and the world outside.” As Drake’s condition deteriorated, nearly all traces of the optimistic young man who wrote Five Leaves Left disappeared. He quit London in the summer of 1974 to return to his parent’s house in Tanworth-in-Arden in Warwickshire where he would sit out his remaining months.

Boyd, who had taken a job in California a few years previously, returned to England in July 1974 to find Drake in a forlorn state. “There was a huge difference in him,” he remembers. “It was shocking to see and he looked terrible. By then I thought the only therapy I could offer was recording his songs.”

Of the final four songs Drake wrote before his death, ‘Hanging On A Star’ was the most accusatory about his career decline. “The song asks, ‘Why do you leave me here when you deem me so high?’,” recalls Boyd. “I think it is directed at me, he wanted to know, ‘Where’s my life? Where’s my money and success?’ The song is directed at me and everybody else who told him he was destined for success.”

“For me, he wasn’t enigmatic,” remembers Thompson. “It was very clear what he was like. He was clinically depressed; there was no mystery about it. We did try to help but it was obvious it was going to be no good. “I told his sister once [actress Gabrielle Drake], I tried

really hard to get through to him. She said – imagine what it was like for her family. It was just one of those situations that felt hopeless. I wasn’t surprised when I heard the dreadful news.”

In the early hours of Sunday, November 25, 1974, Nick Drake went downstairs to the kitchen of his parents’ house to eat some cornflakes. Unable to sleep, he took some of the

orange Tryptizol tablets used to treat his depression. Then he took some more. And then he took too many.

When Drake’s mother, Molly, went into his room at midday to wake him, she found him lying prostrate and semi-naked across his bed. The life of Nicholas Rodney Drake was over. A sealed envelope addressed to one of Drake’s close female friends lay nearby, but there was no note to confirm if he intended to take his life.

“People perceive what he was like and what he meant to do that night,” says Thompson. “But nobody will ever know, so all we can do is celebrate the things we are left with. We could talk forever about why he died the way he did.”

The final words go to Boyd: “A lot of things are easier to see in hindsight. Perhaps the wrong decisions were made by those close to him and he had every right to feel let down. But the people who know his songs know what a wonderfully gifted man he was. It’s only right he’s posthumously acknowledged for his music. I hope these concerts will go some way to restoring his name.”

(First published in The Big Issue in January 2010)