09/11/2009

“When the shit hits the fan,” intones Kelly Jones to The Big Issue, “that’s when people come out and start shouting. It’s cause and effect isn’t it? Whether it’s the miners’ strike or something else happening, I’m not surprised that a lot of this stuff with protests, strikes and upheaval like in the ‘80s is coming back again. When there’s not much else to do people can only sit around and talk for so long.”

As soundbites go, Jones’ assessment of the parlous state of Britain’s economy and creaking race relations isn’t so much a rallying call to action as a dire warning about what can happen when good people sit back and do nothing.

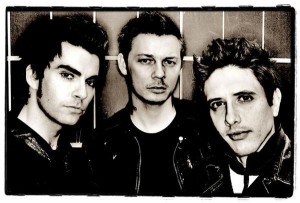

Jones and founding Stereophonics band member Richard Jones (no relation) are taking time out from their snowballing schedules to meet The Big Issue at RAK Studios in North London on an overcast October afternoon.

The studio’s list of previous occupants reads like a hall of fame for British music. Everyone from Pink Floyd to The Jam, The Smiths, Radiohead, Paul McCartney and Depeche Mode has used the facility over the years. Tucked away on a leafy side street a stone’s throw

from Regents Park, The Big Issue finds Kelly and Richard in RAK’s cavernous studio three.

Dressed in his ever-present close-fitting leather jacket, jeans and boots combo, Kelly’s slight build makes him seem doll-like. A tiny triangle of coral pink t-shirt peaks out from the

top of his zipped-up black jacket, seemingly protecting him like Batfink’s shield of steel.

He’s conspicuously shorter than his towering bass player band mate Richard, whose few but wise words second guess what Kelly is about to say throughout the interview. The duo’s near-psychic ability to read each other has been forged over 17 years in the same band.

The Welsh-Argentine quartet is on the verge of releasing its seventh studio album, ‘Keep Calm And Carry On’. The band’s first since 2007’s ‘Pull The Pin’, the title was pinched from a shelved wartime poster that Winston Churchill’s government planned to release if

Hitler’s Third Reich had invaded Britain.

In today’s context, while the country isn’t facing an imminent invasion threat, Jones finds a soothing undertone to the album title’s simple five word message. Situations in life, however desperate, can and will be overcome.

“The title of the record is always the last thing that happens,” he says glancing for reassurance towards Richard. “I think subliminally in hindsight [the title] did represent quite a few songs on the record and maybe the state of the country right now.

“I don’t think it has to refer to a severe dark period to make sense that you’ve come out the other end,” he ponders. “We’ve all been though different journeys and got to certain points. But I think that message, keep calm and carry on, can be a great morale booster

to anyone. I think you can pretty much relate it to anything.”

If Kelly has personally found some comfort behind Churchill’s wartime words, he isn’t letting on. The Stereophonics near-masochistic love of touring has caused many ups and down over the last 10 years, helping them score five number one UK albums in a row,

play endless world tours and tour with the likes of rock royalty The Rolling Stones and The Who.

But there’s a price to pay for everything. Kelly eventually sacked his band mate and long time friend Stuart Cable in 2003 after the drummer’s erratic behaviour threatened to tear the group asunder. Lineup changes followed with the addition of Argentinean Javier Weyler as Cable’s replacement and fellow countryman and second guitarist Adam Zindani.

Now the father to two daughters, Lolita and Misty, Kelly split with his partner and his daughter’s mother, Rebecca Walters, in 2007. Well known for his reticence about his personal life, Kelly’s feuds usually unfold in his music, as the content of the journalist-bating ‘Mr. Writer’ and ‘Rainbows and Pots of Gold’ testify.

He describes fatherhood as “The hardest job ever,” but one he loves every minute of. “I love the perspective it gives me really, I love how it helps you prioritise what’s important in your life. What I find hard is how I’m absolutely fucking completely exhausted all the time. When you come back off tour you want to be there for everything but your body doesn’t sometimes allow you to.”

‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ is no huge departure from the Stereophonics sound, but it is a return to the group’s rockier roots. Opener ‘She’s Alright’ delivers grinding guitars set to a rasping vocal from Jones; ‘I Got Your Number’ is a menacing growl of a tune that finds

the singer warning, “I’ve got your number, you’re a fake.”

The album’s lead song, ‘Innocent’ has already become a fan favourite. It details a teenage Kelly growing up in and around the narrow streets of the former mining town Cwmaman. The voice of youth tells him “everything is possible…nothing’s gonna beat you in this life,”

before the song unravels its sad conclusion it’s about the loss of a friend to drugs.

Live favourite ‘Trouble’ is a whirlwind of drums, low slung bass and workaholic guitars; it’s great fun for the band to play by all accounts, despite its worryingly similar-sounding chorus to mid-90s bubblegum pop duo Shampoo’s song of the same name. It’s about as political as the band gets on the album, couching Kelly as the outsider returning to find his hometown in the grip of a suffocating recession. Its melody treads a fine line between infectious and annoying.

After the group finished its mammoth 18 month touring stint for ‘Pull The Pin’ and greatest hits collection ‘Decade In The Sun’, Kelly returned to Cwmaman to find a worrying slide in the town’s fortunes.

Kelly and Richard both admit shock on returning after so long away to find the community that was the inspiration behind the small town tales on the group’s excellent debut, ‘Word Gets Around’, was in such a bad state.

“I noticed quite a drastic change” Kelly says in a barely audible mutter. “The factories closed down and moved out and the unemployment went sky high really. I think people didn’t have a lot to do; the pubs all closed down and then there was only the working men’s club left.

“The community, which was a community where people would go and socialise with each other was beginning to end,” he says. “An amazing community began to diminish. I think that is quite sad because the character’s that came out of those places were incredible;

good, bad, funny or tragic that was what it was all about and I think that community aspect has gone. When I wrote that first album that was still thriving.”

Both Kelly and Richard say the band has “never been political”, but know at the same time that it hardly exists in a bubble. “Labour is in trouble in a major way and things will change

considerably in Wales next year no matter what now,” Kelly says before looking skyward and adding, “it’s kind of due, isn’t it?”

“I was taught by my grandfather never to talk about religion or politics at the dinner table,” Kelly says. “But I think a lot of people in Wales will be left wondering how they can rebuild their lives after what’s gone on.”

Richard interjects: “We’ve always stayed out of politics [but] there is going to be a big change next year. But I’m of the frame of mind that politicians are all the same.”

“Yeah, I agree with that,” Kelly adds authoritatively.

The Big Issue meets Kelly and Richard in the week that an anti fascist protest took place in Swansea against the Welsh Defence League. It’s the same week that BNP leader Nick Griffin is due to appear on the BBC’s ‘Question Time’ programme.

They’re both reluctant to be dragged into a debate about Britain’s far right movement, but they do give an answer of sorts about why some young people are getting sucked in by the BNP’s rhetoric. “I think these young lads don’t know who to look for trust or support or

anything,” Richard offers. “When things aren’t going the right way for a group

of people, they look around for answers in places they wouldn’t normally look.”

Kelly chips in that it’s the lack of decent role models in government that’s creating political apathy: “But that’s the problem, there’s nobody out there worth going,’ fuck yeah, I’m with them’ for. You could see it in America when Obama got in. It was like a complete thank the fucking lord somebody has something to say. But when was the last time that happened over here?”

The following silence tells its own tale.

Looking back over the last 15 years, Kelly and Richard say they were fortunate to break through at a time when most bands coming out of Wales were instant media gold. But they deny ever holding a secret powwow with the Ma nic Street Preachers, Catatonia and Super Furry Animals to help launch Cool Cymru’s assault on the indie charts.

“It just happened,” Kelly says with a chuckle. “You couldn’t get four or five more different sounding bands. It wasn’t like the Seattle scene or Britpop where the music sounded similar, it was about where we came from.

“All of us were proud about what it did for Wales. But when you’re Welsh you’re always looking over your shoulder being suspicious of things like success,” he says. “You’re afraid of being part of any scene because when it folds, you tend to go with it.”

But if he had to give the teenage Kelly Jones some advice, what would it be? A long, thoughtful pause follows as he shuffles awkwardly in his chair. “Part of the thing when you’re in a band is you’re frightened to stop because the fight involved to come back is harder than trying to continue,” he says. “I would tell myself, don’t worry so much

about it all. It will be alright.”

Kelly Jones keeping calm and carrying on, then? You wouldn’t bet against it.

(First published in The Big Issue in November 2009).