23/11/2009

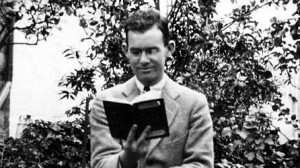

The truth was everything to Gareth Jones. The Barry-born Welsh investigative journalist led a short but highly eventful life that ended in his murder in the wilds of Mongolia in 1935 aged 29. It was the price he paid for his reportage in Communist Russia and Nazi Germany in the 1930s, as he selflessly helped expose one of the gravest crimes against humanity the world has ever seen.

Unravelling the ultimate legacy of Gareth Jones has only just begun. In his lifetime his work was cruelly discredited by other journalists, jealous at his connections and incredulous that the gravity of what he reported could possibly be true.

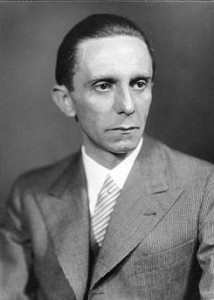

Jones’ picaresque career includes the time he shared a plane with Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels in February 1933, hours after Hitler was made Chancellor of Germany. Jones later interviewed the Nazi propaganda minister after a hysterical, 25,000- strong rally in Frankfurt.

He also became a personal aide to former Prime Minister David Lloyd George, aged only 25, and was once photographed alongside shamed US president Herbert Hoover outside the White House. Jones could also count the wife of Lenin and American newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst among his interviewees.

But his single greatest achievement was almost single-handedly exposing to the world the brutal reality of Josef Stalin’s regime, when he covertly travelled to the Ukraine in the early 1930s to report on The Great Famine (also known as the Holodomor) which killed an estimated five million of the Communist dictator’s countrymen. For the first time ever, Jones’ many diaries are on public display to help cast new light on the personality and career of a man who, in the words of his friend Lloyd George, “died because he knew too much.”

Nigel Linsan Colley, great nephew of Gareth Jones and the person who’s done more than anyone to Welsh investigative reporter Gareth Jones believed in the truth. In the early 1930s, he travelled through Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Soviet Union recording the grim realities of nascent dictatorships.

“I think these diaries were destined to resurrect Gareth’s memory,” Colley says of the pencilled notes found in a dusty old suitcase in the house of Jones’ elder sister in Barry in 1990. “I think even [when he wrote them] he understood how important they would one day become.

“We have the benefit of hindsight and history, but Gareth was living it. There is great serendipity in his story and it’s one that proves that the pen was mightier than the

Soviet sword.”

Jones’ diaries are on display until next month in the Wren Library at Cambridge University’s Trinity College, where he was once a student. Colley says there are no firm plans to hold an exhibition of Jones’ work in his native Wales, but the day is surely inching closer.

The National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth, which already houses many of Jones’ documents, says it has no immediate plans to hold an exhibition of his life and work.

But the interest in the journalist’s work will reach a new level when Ukrainian director Sergey Bukovsky’s documentary about the Holodomor, The Living, gets its Welsh premiere at Cardiff’s Chapter Arts Centre in January.

Born Gareth Richard Vaughn Jones on August 13 1905 in Barry, Jones quickly demonstrated a highly inquisitive and academic flare. Graduating from the University of

Wales, Aberystwyth in 1926 with a first class honours degree in French he went on to Trinity College Cambridge in 1929 and gained the same result in French, German and Russian.

But he was flung into the world of work at a time of devastating financial upheaval. Unable to find regular work as a journalist during the Great Depression, Jones, through close family friend and fellow Welshman Thomas Jones, was introduced to the former Prime

Minister David Lloyd George.

His talents quickly earned him an internship. Jones’ close association with Lloyd George’s Liberal Party in the early 1930s was the making of him.

“From then on, wherever he turned up in the world he would be granted interviews with extremely powerful people,” Colley explains. Despite his fascination with Westminster, Jones’ true passion was travel. It was during three visits to Russia between 1930

and 1933 that he uncovered a genocide being inflicted on the Ukrainian people by Stalin’s Five Year Plan.

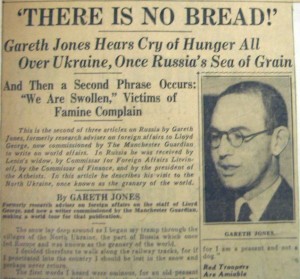

His diaries, and the subsequent newspaper reports in the Manchester Guardian and New York Evening Post, made him the first Western journalist to uncover the horror of Holodomor – Stalin’s devastating “manmade famine” in the Ukraine during 1932-33, which claimed the lives of millions.

Jones’ diary entries exposed the daily horror of people forced to starve in a country that in 1932 produced its largest ever wheat harvest: “Everywhere was the cry, ‘there is

no bread. We are dying,’” his reports read. “This cry came from every part of Russia, from the Volga, Siberia, White Russia, the North Caucasus [and] central Asia. I stayed overnight in a village where there used to be 200 oxen and where there now are six. The

peasants were eating the cattle fodder and had only a month’s supply left. They told me that many had already died of hunger. Two soldiers came to arrest a thief. They warned me against travel by night as there were too many ‘starving’ desperate men.”

Holodomor is now recognised by the Ukrainian government as a crime against humanity. But after exposing Stalin’s purposeful starvation policy against the Ukrainians, Jones

became a marked man who would eventually pay the ultimate price for the success and potency of his work.

“Gareth saw himself as a British citizen, ultimately,” Colley explains. “Perhaps he felt that was enough to protect him from danger. He knew he was likely to have been caught by

the Soviet secret police, but he was a teetotal, devout Welsh non-conformist and for him, the truth mattered.

“I think he felt it was absolutely wicked what was happening and that he had been given this duty to tell the story no matter what personal risk he put himself under.”

Jones’ exposé of the Soviet government’s persecution of its own people eventually led to him being banned from Russia altogether in 1933. It proved a decisive moment; in less than two years, he was dead.

Jones’ Ukrainian stories were mercilessly discredited in the US media, which, perhaps jealous of his contacts, tried to smear the young Welshman with claims he’d

fabricated them. He died knowing his integrity had been undermined.

“He loved writing letters to the newspapers,” Colley says. “He enjoyed having an argument, it was almost a game to him. But I think he was disappointed to be shunned after his stories were printed and much of his work was then overlooked.”

Jones’ ability to be at the centre of a story has acquired legendary status. Within days of interviewing Joseph Goebbels in Frankfurt on February 24, 1933 in a five star hotel, he was sleeping on bug-infested floors of peasants in the Ukraine as he attempted to expose

the horror of Holodomor.

He interviewed the Nazi propaganda minister just three days before the burning of the Reichstag in Berlin; an act that changed Germany forever. In a chilling warning of

what was to come, Goebbels told Jones the Nazis would never surrender their stranglehold on power.

“It’s almost prophetic how Gareth was always in the right place at the right time,” Colley says. “But of course, his death was very much a case of the exact opposite

being true.” The circumstances of Jones’ death are still shrouded in mystery.

Question marks linger over who was with him in Mongolia and why. The identity of Jones’ murderers may never actually be discovered. Colley says there is “absolutely no doubt whatsoever” that he was murdered at the request of Soviet agents. On August 12,

1935 he was kidnapped while travelling with a German journalist “friend” named Herbert Mueller in Mongolia. Both Mueller and Jones were taken by a group of Chinese bandits, but Mueller was released unharmed two days afterwards. It has since emerged that Mueller was a Communist spy employed by Soviet agents supplying arms for Chairman Mao’s Long March in 1934-36.

According to Colley, even the vehicle Mueller and Jones travelled in was owned by the Soviet secret police. While there’s no conclusive proof Mueller sold his friend to the Russians, Mueller certainly had the connections and wherewithal to organise Jones’

death. That he died because of what he knew seems beyond doubt.

“He was an enemy of the state,” Colley says. “He would not have been murdered without the say so from someone in Moscow because of his close association with Lloyd George. I just wonder what would have happened had he survived. Would he have become

editor of The Times or Churchill’s interpreter at Yalta?”

Gareth Jones’ death aged 29 denied the world a fine journalist who, had he lived, would likely have gone on to report further atrocities happening in war torn Europe in the

1940s. The fact that he never realised his full potential still leaves a bitter taste.

Exactly a year ago this week, the Ukrainian president Viktor Yushchenko posthumously awarded Gareth Jones and another British journalist, the late broadcaster Malcolm Muggeridge, the Ukranian Order of Freedom for their “exceptional services”

to the Ukrainian people in exposing Holodomor.

The day that Wales brings home Jones’ diaries and recognises him as a national hero,

and arguably the finest journalist it’s ever produced, must surely come soon.

Gareth Jones’ notes:

Goebbels

We dine together and talk. Charming man; dark brown eyes. Iberian from Rhineland; very narrow head; like South Wales Miner; high brow.

Tremendous humour; very great personal charm; small; with limp. “The S.A. [forerunner to

the SS] defend me just like a big man who has married a petite woman.”

He talks of past days, as the days, the days of idealism.

Autarchy

“We don’t want to lay stress on exports, of course we export to pay for raw

materials; but we want to stretch towards the East.

We want to take the people away from the towns and settle them on the land. To do this we must control the Baltic. That’s why we have (?) the Danzstreuzer [Danzig Corridor in German?] PanzeKreuger We must have a strong Baltic fleet.

It would be in Britain’s interest to allow us to spread to the East. We hope to S????? our

Macht and that Poland will realise that it will be better to give back the Corridor.

If Europe had not seen Ausgeblutet, we’d have had 10 wars. Europe is like a

powder-barrel. Unless the causes? Are removed it will blow up.

We are not so keen on colonies. The mistake of past… was to concentrate on Wetwigtschaften.

Notes on a Nazi Gareth

Jones thought Goebbels a “charming man”. This is an extract of the notes

he took during an interview with the Nazi spin chief in 1933

Germany has two alternatives: Land or Sea Army or fleet East or West Europe or World Cannot do both. Mistake of pre-war days was to try and do both.

It was a vital mistake to build up the fleet. We should have concentrated on the

land. Great mistake to concentrate on export. The days of export are over.

Our expansion to the East need not mean a conflict with Russia. Poland will be

the sufferer.

Propaganda

During the war the German propaganda was abominable; it was in the heads of people were bourgeois and had no connection with the people. A good propagandist must know the roots.

But now the Germans have become the best propagandists in the world. You

watch next week, we’ll flood Berlin with propaganda. I wonder if Goebbels takes things serious; or is it more self-expressionism; love of fights – arguments. Argumentation.

Can imagine him in discussions in South Wales. It is too late to build up an international society. The chance is lost and will never come again.

It seems that the best will be to stick out of Europe. The League of Nations is dead. Hitler

has killed it. Delmer [Daily Express Berlin correspondent] said that a means of defending

Berlin against air attack had been discovered and that there was no fear of consequences of attack on Poland…

Germans do not work out consequences like trench?? Rebirth of Militarism in Germany. Militarism Germany Mixture of Sentimentally Macht Faust: “Es wohnen ach zwei seelen

in meiner Bruist.” [Two souls live, Oh, in my chest]

Goebbels and I drive to station. He says: “We’ll stick to power. Nothing will get us out. From now on there’ll only be Nazi Ministers.

Speeches

Hitler and Goebbels only have a few striking words (Stuhworte) and practically never prepare. Goebbels: “I prepare a speech in 10 minutes. Just a structure. I speak on.

“? I spoke at Mayakowsty’s ???grave, it was only a minute or two before that I thought what I’d say. I thought that I’d describe his life and at each step in life say “and now he lies[?] there? c.f Julius Caesar.

Feel at home with Goebbels. Hitler hunches himself up a little.

(Interview with Nigel Linsan Colley first published in The Big Issue in November 2009. All other materials courtesy of Gareth Jones’ estate).